Pairwise Equity in Apportionment (2018)

Prepared by:

Joseph Malkevitch

Mathematics Department

York College (CUNY)

Jamaica, NY 11451

email:

malkevitch@york.cuny.edu

web page:

http://york.cuny.edu/~malk/

Suppose some apportionment algorithm has been used to assign a collection of seats to parties in an apportionment problem situation.

Suppose A gets a seats and B gets b seats.

B claims to a court that A got more than it was fair to give it. B claims a better distribution of seats would be A gets a-1 and B gets b + 1 seats. How might the court evaluate B's claim?

Let us consider a specific example. Suppose A, B, and C have votes of 1200, 900, and 303, respectively.

|

Divide by:

|

A

|

B

|

C

|

|

|

1200

|

900

|

303

|

|

1

|

1200 1

|

900 2

|

303

|

|

2

|

600 3

|

450 4

|

151.5

|

|

3

|

400 5

|

300

|

101

|

Applying D'Hondt for a house size of 5, yields 3 seats for A, 2 seats for B, and 0 seats for C. The order of the seat being assigned is shown above with numbers on the right.

A gets 3 seats, B gets 2 seats, C gets 0.

A, B, and C's exact quotas are: A's exact quota is 2.4969, B's exact quota is 1.8727, and C;s exact quota is .6305. The ideal district 480.6. If we use the modified district size of 400, we get A = 3, B = 2.25, and C = .7575. Rounding down we have A = 3, B = 2 and C = 0 as required above.

Using St. Lägue (Webster) we get:

|

Divide by:

|

A

|

B

|

C

|

|

|

1200

|

900

|

303

|

|

1

|

1200 1

|

900 2

|

303 4

|

|

3

|

400 3

|

300 5

|

101

|

|

5

|

240

|

180

|

60.6

|

A gets 2 seats, B 2 seats and C 1 seat.

The total vote here is 2403. A's exact quota is 2.4969, B's exact quota is 1.8727, and C's exact quota is .6305. Rounding fractions up which exceed .5 gives A 2 seats, B 2 seats and C 1 seat, which agrees with the table method approach above.

Consider the apportionment A = 3, B = 2, and C = 0.

Let us use the measure seats per people to measure fairness as it applies to A and C:

|(3/1200) - (0/303)| = .0025

Now consider the apportionment A = 2, B = 2, C = 1.

Now compute the seats per people measure as it applies to A and C:

|(2/1200) - (1/303)| = .0016

Hence, we conclude that the apportionment A = 2, B = 2, and C = 1 is more fair than the apportionment A = 3, B = 2, C = 0 for the measure representatives per person. It turns out that if one measures inequity between pairs of states using seats per person as a measure, then one must apportion using St. Lägue/Webster to get the best apportionment.

Here is an example modified in a small way from the 6th edition of Mathematical Excursions, by Tannenbaum and Arnold. We have a parliament with 40 seats, h = 40, and five parties which received 400,000 votes. Thus, the ideal district size is 1 representative for 10,000.

|

State

|

A

|

B

|

C

|

D

|

E

|

Total

|

|

Population

|

140,200

|

105,100

|

65,100

|

54, 800

|

34,800

|

400,000

|

|

Exact quota

|

14.02

|

10.51

|

6.51

|

5.48

|

3.48

|

40

|

|

Huntington-Hill

|

14

|

11

|

7

|

6

|

4

|

42

|

|

Webster

|

14

|

11

|

7

|

5

|

3

|

40

|

|

Adusted quota d=10,030

|

13.978

|

10.478

|

6.491

|

5.464

|

3.47

|

|

|

Huntington-Hill

|

14

|

10

|

7

|

5

|

4

|

40

|

Note that the two apportionment methods agree on all the parties except those for parties B and E. Now, consider the two parties B and E with respect to the measure, seats per people.

When B = 11 and E = 3 we have:

|(11/105,100)-(3/(34,800)| = .00001846

while for B = 10 and E = 4 we have:|(10/105,100) - (4/34,800)| = .00001980

so with this measure the Webster apportionment is fairer than the Huntington-Hill apportionment, since .00001846 is smaller than .00001980.

Now let us compute the minimum of 11/105,100 and 3/34,800. 11/105,100 is .0001047 while 3/34,800 =.0000862 so 3/34,800 is smaller.

So taking .00001846 and dividing it by 3/34,800 we get .2141.

Now let compute the minimum of 10/105,100 and 4/34,800. 10/105,100 = .000095 while 4/34,800 = .000115, so 10/105,100 is smaller.

So taking .00001980 divided by 10/105,100 we get .2081. Now we see that the Huntington-Hill apportionment, measured via relative seats per voter is smaller than that for the Webster apportionment.

To summarize, in this example, Webster is a better apportionment for absolute difference of seats per people while Huntington-Hill is a better for relative difference of seats per voter.

It turns out to be a general theorem that for pairwise equity of parties (states) each of the different methods (Adams, Dean, Huntington-Hill, Webster, Jefferson) is optimal when measured by some absolute measure of equity. However, Huntington-Hill is optimal when measured by all of the relative measures that are optimal in the absolute cases.

Much of the theory here was developed by E.V. Huntington a mathematician who taught at Harvard University. Huntington had looked into the 32 ways that the inequality pi/pj > ai/aj (where the population of state i, is pi and the number of seats given state i is ai) could be rewritten by "cross multiplication." He worked out the different measures of "inequity" between pairs of states that could be used in this way. He observed that in a comparison between two states who had average district sizes of 100,000 and 50,000 compared with 75,000 and 25,000, the absolute difference is the same. However, he thought that the inequity was "worse" in the second case because 50000/25000 is 2 while 50000/50000 is 1. The relative difference to Huntington seemed a better measure. (Relative difference between x and y being defined as |x -y|/min(x,y).) Of the absolute differences the two most "natural" are |pi/ai - pj/aj| which is optimal when Dean's method is used and |ai/pi -a/pj| which is optimal when Webster's method is used.

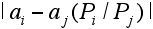

For the measure

Adams method is optimal.

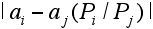

For the measure

Dean's method is optimal.

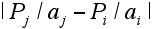

For the measure

Huntington-Hill is optimal.

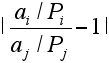

For the measure

Webster is optimal.

For the measure

Jefferson's method is optimal.

To supplement the example worked out above you may want to also look at the analogous work in regard to the example below where the numbers are slightly changed. (These numbers are also due to Tannenbaum and Arnold.) Here, the divisor must be adjusted to complete the Webster apportionment while in the previous version the divisor had to be adjusted to complete the Huntington-Hill apportionment.

|

State

|

A

|

B

|

C

|

D

|

E

|

Total

|

|

Population

|

140,800

|

104,800

|

64,800

|

54, 800

|

34,800

|

400,000

|

|

Exact quota

|

14.08

|

10.48

|

6.48

|

5.48

|

3.48

|

40

|

|

Huntington-Hill

|

14

|

10

|

6

|

6

|

4

|

40

|

|

Webster

|

14

|

11

|

6

|

5

|

3

|

38

|

|

Adusted quota d=9965

|

14.13

|

10.517

|

6..503

|

5.499

|

3.492

|

|

|

Huntington-Hill

|

14

|

11

|

7

|

5

|

4

|

40

|

Above, we looked at fairness in terms of comparisons between two states, and measuring pairwise equity from different points of view (e.g. relative and absolute differences; using different expressions involving claimant populations and claimant seats). However, we could also treat apportionment as a global optimization problem. Compute among all different ways to apportion 40 seats to 5 claimants based on the data above, choose that method that minimizes the sum of the differences in absolute value between the ideal district size (total population divided by total number of seats h) and the size of the district based on the number of seats actually assigned and the population of the claimant state. Of course, there are other measures that could be used for this global optimization. Different measures will typically require that one use different methods.

References (not updated recently):

Abeles, F., C.L. Dodgson and apportionment for proportional representation, Bull. Ind. Soc. History of Math., 3 (1981) 71-82.

Anderson, M. and S. Fienberg, Who Counts? The Politics of Census-Taking in Contemporary America, Russell Sage Foundation, New York, 2001.

Baily, W., Proportional Representation in Large Constituencies, Ridgeway, London, 1872.

Balinski, M., The problem with apportionment, J. OR Society of Japan, 36 (1993) 134-148.

Balinski, M. and S. Rachev, Rounding proportions: rules of rounding, Numerical Functional Analysis and Optimization 14 (1993) 475-501.

Balinski, M. and S. Rachev, Rounding proportions: methods of rounding, The Mathematical Scientist 22 (1997) 1-26.

Balinski, M. and V. Ramirez, Parametric methods of apportionment, rounding and production, Mathematical Social Sciences 37 (1999) 107-122.

Balinski, M. and V. Ramirez, Mexico's 1997 apportionment defies its electoral law, Electoral Studies 18 (1999 117-124.

Balinski, M. and H. Young, A new method for congressional apportionment, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., 71 (1974) 4602-4606.

Balinski, M. and H. Young, The quota method of apportionment, Amer. Math. Monthly 82 (1975) 701-730.

Balinski, M. and H. Young, The Jefferson method of apportionment, SIAM Review 20 (1978) 278-284.

Balinski, M. and H. Young, On Huntington methods for apportionment, SIAM J. Applied Math. 33 (1977) 607-618.

Balinski, M. and Young, Apportionment schemes and the quota method, Amer. Math. Monthly 84 (1977) 450-455.

Balinski, M. and H. Young, Stability, coalitions, and schisms in proportional representation schemes, Amer. Pol. Science Rev. 72 (1978) 848-858.

Balinski, M. and H. Young, Criteria for proportional representation, Operations Research 27 (1979) 80-95.

Balinski, M. and H. Young, Quotatone apportionment methods, Math. of Operations Research, 4 (1979) 31-38.

Balinski, M. and H. Young, The Webster method of apportionment, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., 77 (1980) 1-4.

Balinski, M. and H. Young, Apportioning the United States House of Representatives, Interfaces 13 (1983) 35-43.

Balinski, M. and H. Young, Apportionment, in Operations Research and the Public Sector, S. Pollack, M. Rothkopf, and A. Barnett, (eds.), Handbooks in Operations Research and Management Science, Volume 6, North-Holland, Amsterdam, p. 529-556.

Balinski, M. and H. Young, Fair Representation, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1982, (2nd. ed.), Brookings Institution, 2001.

Balinski, M. and H. Young, The Apportionment of Representation, in Fair Allocation, H. Young, (ed.), Proceedings of Symposia in Applied Mathematics, Volume 33, American Mathematical Society, Providence, 1985.

Bell, M., Relative Difference and the Dean Method: A Comment on "Getting the Math Right," 62 Vand. L. Rev. En Banc 1 (2009).

Bennett, S., et al, The Apportionment Problem, COMAP (Consortium for Mathematics and its Applications), Lexington, 1986.

Birkhoff, G., House monotone apportionment schemes, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sciences, 73 (1976) 684-686.

Bliss, G., and E. Brown, L. Eisenhart, R. Pearl, Report to the President of the National Academy of Sciences, Feb. 9, 1929, in Congressional Record, 70th Congress, 2nd session, 70 (March 2, 1929) 4966-67.

d'Hondt, V., La Répresentation Proportionnelles des Partis par un Electeur, Ghent, 1878.

Dixon, R., Democratic Representation: Reapportionment in Law and Politics, Oxford U. Press, London, 1968.

Dodgson, C., The Principles of Parliamentary Representation, Harrison and Sons, London, 1884 (Supplement, 1885, Postscript to Supplement, 1885.)

Droop, H., On Methods of Electing Representatives, Macmillan, London, 1868.

Edelman, P. Getting the math right: Why california has too many seats

in the house of representatives. Vanderbilt Law Review, 59:297-346, 2006.

Eisner, M.,, Methods of Congressional Apportionment, UMAP Module 620, COMAP (Consortium for Mathematics and its Applications), Lexington.

Ernst, L, Apportionment methods for the House of Representatives and the court challenges, Management Science 40 (1994) 1207-1227.

Halacy, D., Census: 190 Years of Counting America, Elsevier, New York, 1980.

Hare, T., The Election of Representatives, Parliamentary and Municipal, London, 1859.

Hart, J., Proportional representation: Critics of the British electoral system 1820-1945, Oxford U. Press, Oxford, 1992.

Hoag, C. and G. Hallett, Proportional Representation, Macmillan, New York, 1926.

Humphreys, J., Proportional Representation,, Methuen, London, 1911.

Huntington, E., The mathematical theory of the apportionment of representatives, Pro. of the National Academy of Sciences, 7 (1921) 123-127.

Huntington, E., The mathematical theory of the apportionment of representatives,, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sciences, 7 (1921) 123-127.

Huntington. E., A new method of apportionment of representatives, Quart. Publ. Amer. Stat. Assoc, 17 (1921) 859-1970.

Huntington, E., The apportionment of representatives in Congress, Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 30 (1928) 85-110.

Huntington, E., Discussion: The Report of the National Academy of Sciences on Reapportionment, Science, May 3, 1929, pp. 471-473.

Huntington, E., The Role of Mathematics in Congressional Apportionment, Sociometry 4 (1941) 278-282.

Lucas, W., The Apportionment Problem, in Political and Related Models, Springer-Verlag.

Mayberry, J. Quota methods for congressional apportionment are still non-unique, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 74 (1978) 3537-3539.

Morse, M. and J. Von Neumann, L. Eisenhart, Report to the President of the National Academy of Sciences, May 28, 1948, Princeton, N.J.

Owens, F., On the apportionment of representatives, Quart. Publ. of Amer. Stat. Assoc. 17 (1921) 958-968.

Oyama, T., On a parametric divisor method for the apportionment problem, J. Operations Research of Japan 34 (1991) 187-221.

Oyama, T. and T. Ichimori, On the unbiasedness of the parametric divisor method for the apportionment problem, J. Operations Research of Japan 38 (1995) 301-325.

Poston, "The U.S. Census and Congressional Apportionment, Society, (1997), 34(3): 36-44

Rae, D., The Political Consequences of Electoral Law, Rev. Ed., Yale University Press, New Haven, 1971.

Saari, D., Apportionment methods and the House of Representatives, Amer. Math. Monthly,, 85 (1978) 792-802.

Saari, D., The Geometry of Voting, Springer-Verlag, New York, 1994.

Stevens, J., Opinion in United States Department of Commerce v. Montana, 112 Supreme Court 1415, 1992.

Stiill, J. A class of new methods for congressional apportionment, SIAM J. Applied Math. 37 (1979) 401-418.

Willcox, W., The apportionment of representatives, Amer. Econ. Rev. 6 (1916) 3-16

Young, H., Equity, Princeton U. Press, Princeton, 1994.